Posted in Blog, Collateral Consequences, Consumer Issues, Housing, Uncategorized

Welcome to the first feature in our South Carolina Housing Stories project! In this series, we will be talking with advocates, community members, and more about housing issues in South Carolina and discuss the need for housing investments in our state.

For our first story, we sat down with Kieley Sutton, a public defender at the Richland County Public Defender’s Office to talk about her nonprofit work at The Rainy Day Fund, an organization dedicated to helping individuals pay basic everyday fees we take for granted. We discuss her work with the Rainy Day Fund and challenges she sees day-to-day in her work.

Part One: About The Rainy Day Fund

_______________________________

Thanks so much for joining us today! Can you tell us a little bit about yourself?

My name is Kieley Sutton, I currently work as a public defender over at the Richland County Public Defender’s Office. I went to Virginia Tech for undergrad, where I got a Spanish degree and then I went to the American University Washington College of Law for Law School. And then I ended up here through a Gideon’s Promise program. It kinds of works like Americorps, but for public defenders’ offices. So I got matched with this office, it was very random.

So that’s how I ended up here and I’ve been at the Public Defender’s office for about 5 years now. We started the Rainy Day Fund, we were incorporated in December of 2020. So right at the end of ’20 and that was kind of, it grew out of the public defense work. We got so frustrated with just seeing so many people who you know have an offer of PTI or time served, but they can’t afford PTI so they’re going to take a conviction. Or you know, couldn’t get an Uber to show up to court. So those little costs that were just preventative from people succeeding. There were a lot of good-hearted people in our office that a lot of people were just paying out of pocket and that was just not a sustainable model and so we got together and started the Rainy Day Fund to address that. So it’s been going strong for about a year now, it’s been really fun.

You started The Rainy Day Fund with your mom as well right?

Yeah, my mom and I started it. She’s really jumped into kind of learning about these issues and you know, she and I would talk a lot about I’d had a client that I bought lunch for or bought clothes for and she just was indignant about the fact that those costs were really adding up. I think a lot of lay-people who aren’t in this work don’t realize how many small costs are just associated with the criminal legal system, like having appropriate clothes to wear to court and getting there and all that kind of stuff. So she knew that people would want to donate if we could just get it together. So she was actually a big driving force behind you know, getting it started, getting our 501c-3 status. And we created a board of people doing this work, both in Virginia and here and that’s been pretty cool.

In 2022, The Rainy Day Fund has provided direct financial support to 16 unique clients to include 25 individuals. They have paid for 12 total nights in a hotel for clients who are on the waitlist for shelter programs and needed bridge housing until their bed becomes available. They have also covered the cost of transportation to court dates, emergency groceries, hygiene and clothing products for folks exiting institutional settings, pre-trial intervention costs, driver’s license reinstatement fees, and more. Their financial contributions to supporting individuals adds up to $808.46 as of today with another $2,539 allocated for drivers license reinstatement fees to cover those requests. In addition to that, they have distributed donated hygiene products, underwear, socks, shoes, backpacks, food, water, bus tickets, etc. to an additional approximately 60 unique individuals.

Source; Kieley Sutton

How many people has Rainy Day worked with since you’ve started?

The way that it works is that we have 2 different types of funding: we have micro-funding, which are payments typically under $80 that are emergency, like right then and there. And then we have macro-funding, which is anything over that that require like more procedural voting and stuff like that. And so, I would say we’ve probably, if I had to estimate, around 50 people since we started and the requests, now that we’re out there a little more, the requests are definitely coming in much faster. So I think we’ll see a lot more requests for help than we have in our first year, kind of coming up pretty soon.

Part Two: How Small Bills Become Big Problems

_______________________________

In learning about Rainy Day’s work, I was thinking a lot about how we take for granted how many small costs that we have on a yearly basis, like the different fees if you go to the DMV. There’s like four thousand expenses it sometimes feels like. Could you go over the most common ones that you see that hold people up in different situations?

I think that the DMV ones that you identified are pretty spot on. If you have a suspended license, your first time is $600 and then a $100 reinstatement fee. Your second time is $1,200 and another reinstatement fee. And then your third time is $2,200 and a reinstatement fee. But after your third time, it becomes a felony. So it can spiral very quickly and your license can be suspended for nonpayment of property taxes or failure to pay child support or failure to pay a $78 speeding ticket.

I think people don’t realize how easy it is for one thing to spiral another and another.

Exactly, yeah. We got a lot of requests and the DMV statutorily cannot waive any reinstatement fees. So there’s no, like breaks. So that’s a big one. We also see, kind of circling into the housing crisis, a lot of folks, there’s a lot of hidden fees with housing. For example, grants will cover your first month’s rent and your deposit, but they won’t cover your application fee. Or they won’t cover the expungement fee to get your background check reduced so that you can get into an apartment or stuff like that.

We also pay for a lot of hotel rooms, that’s another big one because if you are incarcerated or in any kind of institutionalized setting for more than 90 days, the federal definition of homelessness considers you housed. So if you are in jail for 90 days, you cannot go straight into a shelter or straight into an emergency traditional housing program that takes federal dollars because you’re not considered homeless. So you have to spend a night either on the street or in a hotel or something else that would put you back under that criteria to even get into those programs. So people exiting prison or exiting jail after more than 90 days don’t have that option or there’s not enough bed space, so there’s waiting lists, so you could have 2 or 3 days before you can get into a program. And if your choices are on the street, your chances of relapse or your chances of victimization or missing doctor’s appointments just increases. So there’s a huge continuity of care issue that would help people get and remain housed.

With our hotel program, we partner with some of our service programs so we’re able to say like, okay they’re going from jail or somewhere to this hotel so that the service providers know where and when to meet them instead of having to say “where are you wandering around today?”.

There really are just so many details that go unnoticed unless you’re in that situation. You spoke about DMV and housing, are there any other small costs that you’ve noticed? I know like government things like social security cards.

The identity document crisis is a big one, luckily we have partners that have grants to cover that, so the Rainy Day Fund hasn’t had to pay for that. But you know, it costs money to prove who you are so a lot of times if someone is living unsheltered they lose or have their identity documents stolen. And if you don’t have an ID, you can’t get a birth certificate or a social security card. But there is an avenue to kind of get around that. So attorneys can request birth certificates if someone doesn’t have an ID, if you’re like stipulating that that person is who they say they are. So we do a lot of birth certificate requests, so then they can get their ID and then their social and then be eligible for housing or programs.

So several hundred dollars later.

Several hundred dollars later.

Is transportation also part of it?

I mean, it’s all incorporated. Ubers or bus tickets to either programs or to court, like if you’re living out in Lexington and you have to go to PPP downtown, Probation, Pardon, Parole downtown, and you can’t, there’s no bus. So, getting an Uber. I mean, you have housing you know where you are but you can’t get there to check in or you can’t get to your court date or that’s a big problem. We also, you know, the expungement and PTI costs, what I mentioned earlier, is one that we would like to get more into because, you know, if you can afford that $350 expungement fee and clear your record, then you have more opportunities than someone who’s convicted of the same thing but doesn’t have that $350. Or we had, one of our most recent things that we paid for was, we had an 11 year old who was charged with having a weapon on school property. He was being bullied and he brought a BB gun to school to try and like scare the bullies. And his offer was PTI, which was $100, but when you’re 11, who was $100? So we were able to pay that so that he doesn’t have to do the typical adjudication process.

And you know, putting the parents in the position to pay for groceries for the family or their one child’s PTI cost, like that’s not fair. And just, those things that seem appalling and seem like, you know, I got a driving ticket when I was in high school and it was $300 and they took my license for a week. And I was driving really really fast. And that was no skin off my back and that’s not the same for other people. And so I think that that aspect of it can really surprise people that that cost, that ability to escape consequence, or the idea that financial consequence is not really a consequence for a lot of people, is not uniform, that’s not across everyone who’s charged.

I think what we prioritize as the problem is different, you know, for income level. So like, if you get a ticket, it’s like “oh no, that’s on my record forever” or something. Or like for years and it’s gonna cost me money. But then for someone who doesn’t have money, it’s like “oh no, I’m in trouble”. Like, a really harsh difference.

Yeah, the transition between like survival thought processes and planning processes are different you know, when you’re living in poverty, it’s about survival, how do I get through tomorrow and that’s much more, how do I avoid paying this $200, like I can deal with that tomorrow, but I need food today or I need rent money today. Whereas people who are not living in poverty have that luxury of planning.

Do you have a story or two you can share from your work on The Rainy Day Fund that helps showcase this?

Yeah, I mean, there’s so so many. For instance, we had someone who was released from jail, it was a woman who was arrested and the hospital paid for hospital paper scrubs. When she was released from jail, they didn’t give her her paper scrubs back, and so the only clothes that they had to give her were really oversized, dirty men’s clothes that had been left by someone else. So like someone else’s dirty clothes is what they gave her to leave jail in. As she was going into a rehab facility, we were able to buy her clothes that actually reflected her gender identity and made her feel a little bit more human. Like there’s so much dignity in hygiene and in clothing; exiting jail wearing someone else’s oversized, men’s dirty clothes just isn’t a confidence boost. It’s not seeing who you are as a person and meeting you there. So that one was really cool.

We also have had an individual who she had raised enough money for like, the first month in a boarding home, but not enough for the deposit. And most grants (housing assistance) = won’t cover your boarding homes. And so we were able to pay her deposit and she’s been housed since then. It’s been probably close to 8 months now. And so that was really cool. We also have had, I think our first client, the first person that you see on our website, like the very first person, he was someone who fit in between all of the services. He didn’t have mental health issues, he was chronically homeless. But because he didn’t have mental health issues or substance dependence issues, he didn’t meet most of the housing program criteria. And he was elderly, but not so old that like APS or other organizations would get involved. He was congestive heart failure and leukemia and high blood pressure. And so he had all these medical concerns, but none of them were so life-threatening that the hospital would keep him. And I worked with him for probably 2 years, 2-3 years trying to connect him to services. But he just didn’t meet all of the criteria necessary for any programming. And so he just kind of would get his social security check, spend it on a week in a hotel. It would be out and then he would be on the streets for another 3 weeks. And we were able to pay, we were able to get him into a boarding home and pay for a month so that when he started paying the monthly fee when he got his check, so that he wouldn’t get kicked out. And while he was in that boarding home, he had enough of a health crisis that the hospital actually put him on hospice and said he was going to die.

So then he went to a nursing home where between going from a boarding home to a hospital to a nursing home, between the consistent food and access to shelter and access to consistent medication, he’s no longer eligible for hospice because he’s thriving. So what they did was they then moved him back to the boarding home and it was crazy cause shelter really was the only thing that like, the consistency of the shelter, the consistent access to food was the only thing that was keeping him so up and down. And so he’s been housed since, he was the first person that we helped, so he’s been housed since 2020. His blood pressure’s regulated, his leukemia’s treated, his congestive heart failure; I don’t how much this is true, but they said it was like reversed or no longer there. He got hearing aids for the first time, he got dentures for the first time in years, he’s got teeth now, he’s really excited and glasses. The first picture that we have of him is in a wheelchair and he walks unassisted now. So just like, that ability to say, “we’ll get you a month of stable consistent housing” led to a complete treatment and now he’s totally functional, doing what he wants to do and knowing everyone him.

It’s so frustrating that you literally have to be like on the cusp of dying to get services. Like, for all intensive purposes, he seemed to check plenty of boxes.

Yeah, it would like he would check one or two boxes for each organization, but they needed five or something. So he was just the perfect person who needed help but was just right there in the middle of all of the cracks. And so that kind of experience is exactly what the Rainy Day fund tries to address, is those people who are in the middle and just, it was like $200 that made a difference.

That kind of goes back to what we were talking about earlier, just like, a few hundred could stop a spiral.

Yeah it absolutely can. And there are people out there who want to give and they just didn’t know where to. And a lot of our strong partner organizations are great, but then again, they don’t serve everybody, there are still those people in the cracks. And so our hope is just to supplement what’s out there.

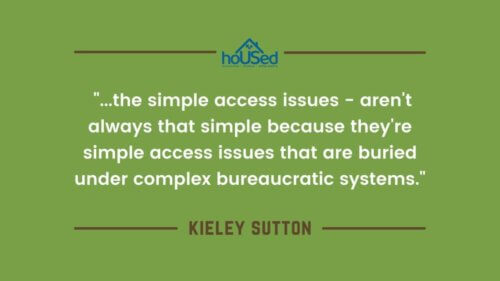

We see it in our work often, questions like “where can I more easily get access to my social security card?” or “why is it taking like 6 months online?” Just simple access issues that is delaying everything.

And that – the simple access issues – aren’t always that simple because they’re simple access issues that are buried under complex bureaucratic systems. And so that’s why our board, we have lawyers, we have public defenders and private lawyers, we have civil and criminal lawyers, we have social workers, we have homelessness outreach workers, we tried to really bring in arrange of skills so that when we’re meeting up against these bureaucratic systems, we have someone who either has experience navigating them or has the ability to figure it out because a lot of our clients might want their social security card, but when they’re closed and it costs, you have to get all these other documents first, it’s difficult to navigate by yourself. There have been times when I’ve had clients where I’ve had to get the general counsel of the DMV for multiple states on the phone. Like clients aren’t going to be able to do that by themselves. So it’s those complex systems that are set up to keep people in the boxes that the system wants them to be in. It requires a certain level of knowledge to navigate them and that’s frustrating on top of everything.

Part 3: Housing Challenges in South Carolina

_______________________________

You were talking a little bit about specific to community needs. What are you seeing that you feel is more specific to South Carolina, if anything? Or are there things that you’re seeing more commonly than others.

Yeah, specifically to housing is that there isn’t any. We can help folks get their identity documents together and you know, right now there a lot of those emergency housing vouchers out there, but no one can find an apartment to take the voucher or they found an apartment, but because they’ve got a 20 page rap sheet of all homelessness associated trespasses or prohibited acts in a city park, they’re not passing the background check. Which brings into the expungement issue. There’s not a lot of affordable housing. There’s only really two shelters that do emergency same-day beds, but for Transitions, if you’re not on the bed list by 9 AM, you don’t really get in. So say if you get released from jail at noon, well that’s not an option. Oliver Gospel’s very similar, if you’re not lining up ahead of time, those beds fill up. And that’s great that they’re full because that means they’re serving as many people as they can, but the amount of folks in need of either emergency housing or affordable housing, because those are two slightly different demographics, it’s just not available to sustain the population and to get people housed and sheltered. So, I think that’s unique here, like we can pay your deposit or there’s money out there to help with rental assistance, but the affordable housing is not there.

What other housing challenges are you seeing that you feel are important to get out there and for people to understand?

In the whole state, I’m only aware of one programming opportunity that works with people who are on the registry and that’s in Charleston. You know we have a lot of folks experiencing homelessness here who are on the registry, it’s not a lot, but there are enough that are very visible folks experiencing homelessness that they don’t have any housing opportunities here at all. So I think that that’s an issue, I think that shelter space and transitional housing space is an issue. I think that one thing that we really struggle with is finding, when you have folks who are married without kids, or who are partnered without children, there are not a lot of spaces for those people. We got a call about a couple who had lost their business during COVID and had just been evicted from their home and were living in their car. And they were like any other mom-and-pop store couple, but they can’t get into a shelter together because they’re married. And so they’re very much in need of support of programming like that, but we can’t get them in anywhere. And so the option is to put them in a hotel until they get approved for Section 8 or some other kind of housing assistance. But, the cost of that is prohibitive. So that’s a unique issue or some folks who have been unsheltered for so long, they partner up for safety and it’s really hard to separate them. Whether or not you agree with it, that’s something that is preventing them from seeking services. So that’s a unique kind of population I think, there’s not a lot of options for.

Again, going back to just like, so many ways you can accidentally get lost in the system, not even doing anything wrong, it’s just like that’s just how it is.

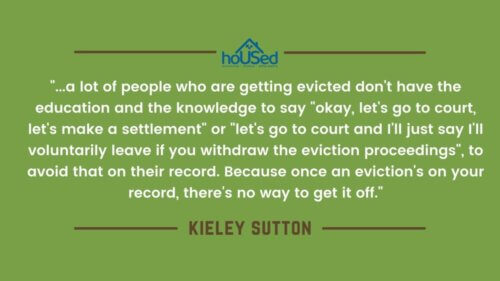

Another thing is that the understanding of how to navigate being evicted; a lot of people get behind on rent and you can’t necessarily expect every landlord to take those losses. So I understand that. But a lot of people who are getting evicted don’t have the education and the knowledge to say “okay, let’s go to court, let’s make a settlement” or “let’s go to court and I’ll just say I’ll voluntarily leave if you withdraw the eviction proceedings”, to avoid that on their record. Because once an eviction’s on your record, there’s no way to get it off.

There’s a new housing court in Charleston where they’re supposed to have pro-bono attorneys that are trying to help people navigate and understand how to kind of avoid that eviction on their record. I would love to see that here because we get so many people, even through homeless court, or other programs where their big hurdle is an eviction on their record. There’s nothing you can do about it once it’s there. And so, the education piece and working with folks who are up against those eviction proceedings or those show-cause proceedings that could lead to an eviction and helping them understand how to best preserve their own ability to get housing in the future. I’ve had so many clients who get their eviction papers and just leave. And then the eviction goes through, but they’ve left all their stuff, they’ve left the apartment and now they’ve got an eviction on their record because that paperwork scares them and they don’t want to court or they don’t know how to go to court or they don’t how to read the papers. And then there’s not much you can after that. Their credit’s ruined, their background check for a new apartment complex is ruined, so even if they do eventually, reach their level of success and they’re ready to go into housing and can pay for housing, can afford housing, they’ve got evictions and all this stuff preventing them from getting there.

Yeah and especially when it’s so competitive right now. It’s very easy for a landlord or whatever just be like, that’s not the case.

Yeah, this city’s [Columbia, SC] emphasis on student housing apartments, especially downtown, which is where also all of our services are, has really pushed our population who’s in need of affordable housing to the outskirts, where there just aren’t the same resources to help keep them connected and the affordable housing is not downtown. I was watching the “No Address” documentary recently and they were talking about how a one bedroom apartment used to be $500-600, which is what the voucher’s are intended to cover. But now one bedroom apartments are $1,300-1,400, so even if you have a voucher, it’s not designed to cover the cost of a one bedroom apartment in Columbia anymore

Housing Choice Vouchers help low-income Americans find affordable housing in the private housing market by reimbursing the landlord for the difference between what a household can afford to pay in rent and the rent itself.

Source: National Low Income Housing Coalition

Also called tenant-based Section 8, the Housing Choice Voucher program is HUD’s largest rental assistance program; it also serves the lowest income people because of deep income targeting guidelines. NLIHC advocates protecting and expanding the housing choice voucher program with the goal of assisting as many extremely low-income households as possible.

What are three things that you think would be good things for people to know or fixes even, that people should be aware of, based on just your experiences with Rainy Day Fund specifically? It can be housing, it can be not too, if you can get one housing, that’d be great, for the purposes of this.

I think I would love for laypeople to just understand that it’s not a matter of willpower. It’s not really a fix, but it is something, the expectation that folks who are unsheltered can just, willpower and hard work themselves out of being unsheltered is not a reality. And so we have a lot of businesses and housing owners downtown that get really frustrated and say, “oh they want to be experiencing homelessness” or “if they just, did Transitions and did the program, it would work.” Well, it’s not that simple. And so, I think that that understanding would be at least, allow for more dialogue on how to fix the issues. Because right now, people don’t understand that identity documents and application fees and access to showers, those things that would require someone to be able to navigate these systems, is a part of the dialogue that’s not there right now. Right now, it’s like “how do we get them into the hospital” or “how do we get them into housing”. Well, in order to get there, we need to address all these stacks first. So, I would really encourage people to look at that. I think there’s a big movement for finding, you know there are a lot of abandoned buildings in Columbia, abandoned malls. And you know, I was at a discussion the other day about how those could be used for, kind of like a community-first model, similar to the one in Austin. Have you heard of that one at all?

I don’t think so.

So there’s this housing-first philosophy, but Austin took it to the next level and it’s called community-first. And so, they have like these tiny homes, some of them are 3-D printed, some of them are storage units. But it’s a community where all of the services are there, there’s a lot more housing, it’s centrally located to the city. And we have the buildings for it here, you know, we have abandoned malls, we have abandoned Walmarts, we have abandoned hotels that could be used for this community-first model. And it’s just a matter of getting the right people at the table to make that happen. And I don’t know how much of that’s being discussed in city council or county council, but I think a community-first model here could really work. The example in Austin is really amazing and you should definitely look at it, it’s pretty cool.

And then my other kind of, vision project is more of a community collaboration holistic approach to every individual. And so right now, I’m back in school getting my MSW. And my goal is to really work with both the legal services and the social services to create a community-based holistic approach to case management. You know, so many times we get clients and we have no idea that they’re working with a service provider, or a service provider is working with someone and they have no idea that their client is missing court because the two worlds don’t communicate very well. And that’s something that we’re really trying to fix in our office through our community partnerships and it’s slow going, but this idea that jail and the criminalization of poverty does interrupt the continuity of care for folks who are trying to get into housing or programming. And so kind of opening that discussion and creating an expectation that someone who is in the criminal legal system also needs social services and vice versa. Someone who is in engaging in social services is likely also wrapped up in the criminal legal system and I’ve had experiences where clients get housing. I’m thinking of one in particular. We got her housing after ten years of being unsheltered and asking for apartments and asking for treatment and we just couldn’t get it and couldn’t get it. And then finally we got it and maybe 6 months later she had a probation revocation and they sent her to prison for a year. And so she lost her housing after 6 months. And so it was like, they have to work together in order to make it work. So when she gets out of prison, her apartment’s no longer there, we have to start over.

So increasing this community collaboration in a way that is well-funded, but also the expectation and the norm and not the exception. So when someone goes to court and they’re experiencing homelessness or they’ve got a charge for something that’s associated with a status offense like trespassing or prohibited acts in a city park, the expectation is that that person will then get holistic, wrap around services for their criminal issues, their civil legal issues and their social issues. And so working in the city to create that system of community collaboration and interdependency in a way that supports a person as a whole. Because you just see like a criminal offense is a symptom of the system, it’s not a symptom of that person. That person has all these needs and all of these collateral issues are happening, but typically it’s because of their status, not because of who they are. And so, creating a community that looks at the person and is able to address their whole need in a way that’s collaborative and has open communication and is a more wrap-around support system. So those are kind of my 3, to sum it up. Understanding that it’s not a willpower issue, a community-first like housing model would be awesome, but then also incorporating a community collaboration expectation of how we work with people who are experiencing homelessness or who are criminal legal system involved.

We want to thank Kieley for taking the time to speak with us about The Rainy Day Fund and her work. Please visit The Rainy Day Fund to learn more about their work and how you can help. You can also follow them on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Additional Resources/Further Reading

The Gap ’22: The National Low Income Housing Coalition’s research on the housing crisis in the US and it’s impact on renters.

Take Action: Use this tool to advance the most possible investment in Housing for the fiscal year.

Learn more about Housing Challenges in South Carolina: Visit our HoUsed Campaign resource page for more information on the housing challenges in South Carolina