Posted in Uncategorized

Welcome to another installment of our South Carolina Housing Stories Project!

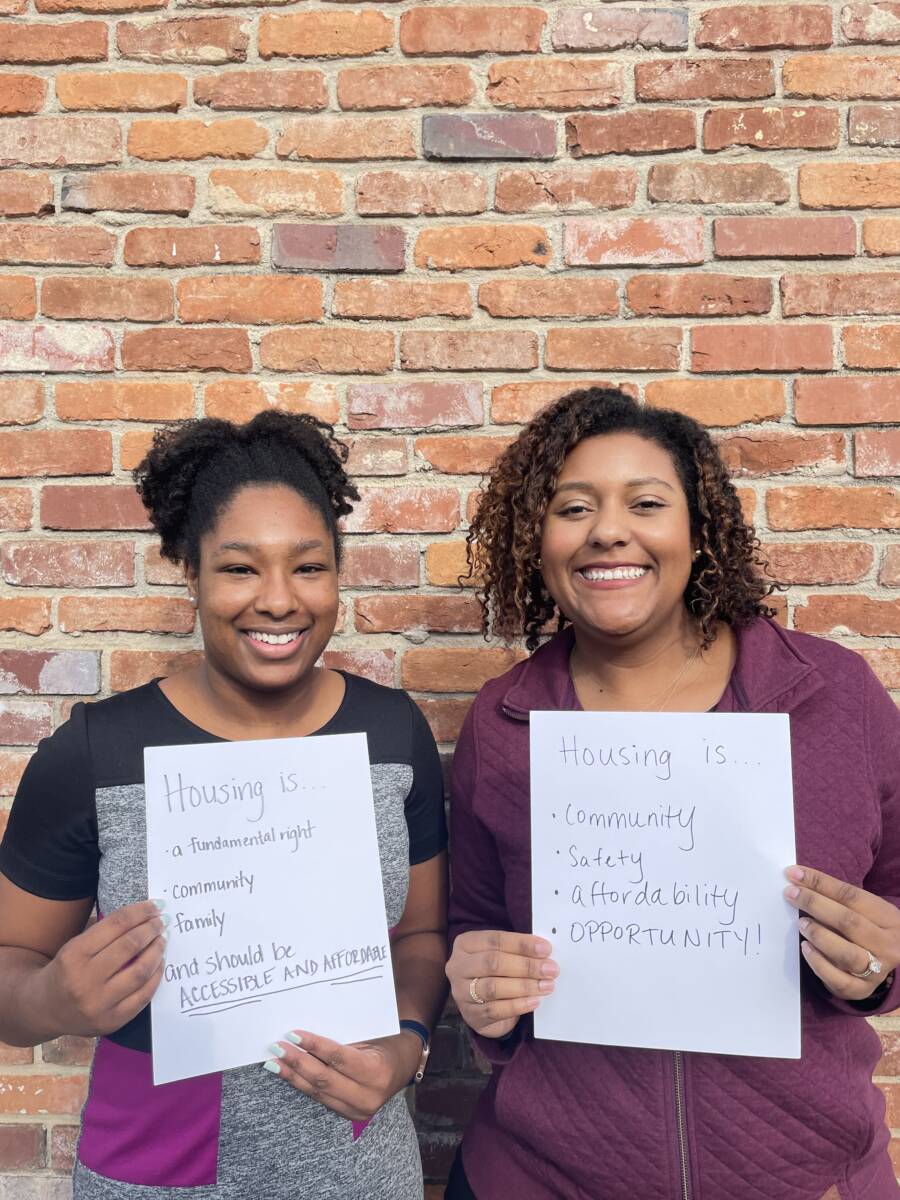

Our Housing Justice Organizer, Sloan Wilson (she/her), sat down with Ashley Blas (she/her) and Glynnis Hagins (she/her) to learn more about the NAACP’s Housing Navigator Program in Columbia, SC. This program connects folks in Richland County with legal and financial help with those facing eviction and housing insecurity.

Thank you both so much for joining me today! Could you tell me a little bit about yourselves and how you both got into this work?

Ashley: Sure. I’m not originally from South Carolina but moved here five years ago because my husband got a job. I’m an attorney, and I ended up meeting Sue Berkowitz and a bunch of other folks. I really liked the work Appleseed was doing. Once I had two children, I left the traditional workforce to be at home with them, but I was looking for volunteer opportunities. When COVID hit, I started getting a lot of pro bono emails, and one of them was from the NAACP. I thought this seemed like something I could do to utilize my skills. But also, it was really important to me; I saw what COVID was doing and how it was wreaking havoc, particularly on communities of color. That’s how I became more and more interested in this work. And I learned more about the program, and I signed on to do it.

Glynnis: I was a teacher before law school. I don’t want to make it seem like it’s the norm, but there are a lot of homeless students – a lot more than you would think. And a lot of them were hidden. They come to school every day and would be just a little bit sleepy throughout the school day, but you never really knew they were unhoused. It was kind of like invisible homelessness. So, when I heard about the housing navigator program and their work to curb homelessness, that really sparked my interest in the program. I started applying for jobs and fellowships, and once I learned more about the housing navigator program, I went through training and started immediately. After I started, Joe Schottenfeld and Martina Tiku at the NAACP encouraged me to do a fellowship with the navigator program. I applied for funding through Equal Justice Works and the Skadden Foundation, and within a couple of months, I got funding through Skadden. Especially in the interview, I think they could tell that this program was really necessary. With the housing navigator work, we’ve helped over 200 people – we lost count of the number. Just that impact alone in a state as small as South Carolina, where it’s only like 5 million people here, so the scope of the program is just amazing.

That’s great! So, can y’all tell me a bit about the NAACP housing navigator program?

Glynnis: A navigator is a community volunteer who helps tenants walk through their housing issues. Currently, we have between 60 and 75 navigators. Usually, a navigator will be assigned a tenant and we’ll call the tenant and ask them about their situation. Where are they living? Are they on the brink of eviction? Has their landlord failed to make repairs? Or, is it something else? If they can’t afford their rent, can we get them access to social services or food assistance?

So we walk them through the various situations, and then we can give them referrals to legal services if they’re facing an eviction, or issue referrals and connect folks with other resources. For example, I helped one of my clients walk through the Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP) application. That isn’t really the basis of the program, but it’s one way that we can help the tenants.

Ashley: Yeah, exactly. Also, you can apply online for legal services, so we’ll see if they need or want help filling out the form online. We want to see if we can connect them to any other resources. So, it’s really kind of holistic in the sense of, we’re looking not just at housing, but other safety nets. Also, we don’t have any eligibility requirements, so we’re able to take anyone who needs assistance.

How do you usually take meetings with clients? What does the process look like for a tenant to get connected with y’all?

Ashley: We contact folks mostly virtually by phone, email, and text.

Glynnis: I think because it was peak COVID when we started, we were trying to do things virtually as much as possible. I actually had one client who had COVID, and I met with him virtually, so folks have been able to remain where they are and receive assistance. Since then, there are many ways people get in contact with us. The more I work behind the scenes, the more I realize this is not just people filling out the intake available online or contacting us through social media. It’s also people hearing from a neighbor or seeing a flier in a local store.

Ashley: One thing I love about the navigator program is the partnerships it has built over time. Like the work Richland Library is doing is incredible; I can call up a social worker there and let them know I have someone who needs help that’s going to give them a call. We also get referrals from the library, which is funny because we refer back to them.

What kind of training do navigators usually go through? What’s it like being both a lawyer and a housing navigator?

Ashley: It’s a few hours, and it’s led by two main lead attorneys. So you go through a PowerPoint slide, and they walk you through all the materials. I did mine virtually on Facetime in 2020. Even though it was a couple of hours I feel like it was a comprehensive training, and Joe and Martina – the two lead attorneys – are always willing to answer questions. I had a million questions, and they were always willing to hop on a call.

They really stress the disclaimer that in this role, you are not an attorney. For example, during COVID, the Biden administration allowed tenants to make declarations to their landlords saying that because of COVID, their financial situation changed, so they could not be evicted. But, the tenant had to actually declare it, and some people thought the administration said that landlords cannot evict anyone while this policy was in place. So I would say that the landlord-tenant act is still in place, and you can’t not pay rent because your heat isn’t working – that’s not the law in South Carolina. But I can’t say it in that way to the client, so instead, I might say ‘well, the current law in South Carolina is blah, blah, blah’ and ‘are you aware that there is a declaration? Do you want me to tell you more about it?’ I could then explain what would happen if a tenant were to make this declaration to their landlord. That way it’s different from giving legal advice.

Glynnis: Yeah, yeah. I’d say for me, most of my time in this role, I’ve been a law student. It’s only very recently that I became an attorney, so I couldn’t even put on the lawyer hat if I wanted. Like Ashley said, having the knowledge base makes it easier for me to see housing issues like evictions and put people in touch with South Carolina Legal Services. And I can help walk folks through the intake form, so having that knowledge base is nice, but you can’t give legal advice.

“Nationally, if you look at living in South Carolina versus living in California or New York City, this is an affordable place. But if you zoom in and actually look at South Carolina salaries and like how many jobs are available within the state, it looks less affordable.”

– Glynnis Hagins

It’s really such a phenomenal program, especially how it can connect folks to so many different resources in various areas. I’m sure that’s a lot less daunting to clients, having someone on their side tackling these intersecting issues. What issues are you seeing come up the most with folks you work with?

Ashley: I would say there’s a lack of affordable housing here. Also, people just are not making the wages to, you know, be able to find housing that is affordable. I’ve really seen the fragility of many people’s financial circumstances. Like, if your tire blows, you don’t have any money to pay rent. I’ve seen these kinds of things over and over again. I understand the landlord is relying on this income, but my heart is with tenants. A lot of people are just trying to make it as they go, and I think there’s this perception that people aren’t working hard enough. But even with two or three jobs, people aren’t making it.

I also want to mention the scarcity of any sort of safety net. There have been many times we’ve had conversations about sending people to resources, but the funding is dry. We don’t know when the funding is going to drop, so if we’re sending all these people to ERAP and ERAP is closed, what’s the next step? We’ve tried really hard to not send people to dry resources, but it’s made us more creative in finding new places and new resources.

Glynnis: Yeah, a lot of people are being evicted for a failure to pay rent. As soon as someone misses their first payment, the landlord is filing to evict. So during COVID, it was kind of nice that landlords would make that threat but then said if the tenant can get rental assistance, they’ll help out. There was a lot more negotiation. I understand that landlords have bills to pay as well, but I also recognize that these are people’s homes and if they’re evicted, where can they go? So there are a lot of structural issues within the state that definitely need to be addressed, and there’s no social safety net.

So now, all of these community organizations are coming together to make sure people can stay in their housing and have access to funding resources that can help them cover living expenses. Because of COVID, the federal government pushed to make sure that everybody was okay. But for that, I would be concerned about where we would be in this current housing crisis that keeps skyrocketing.

Ashley: And I think people think COVID and the effects of it are over, but really, we’re seeing the ripple effects of everything that’s happened. People who got behind on payments still owe that money. Once someone becomes unhoused, it’s very difficult to get housed again. I think we need to pour more money into the social safety nets we have to keep people afloat, especially during this time. You know, we go to the grocery store too, and we can see that milk is five times more expensive than it used to be. It makes you think about how that’s impacting the people we’re helping.

Yeah exactly. Like Glynnis said, thinking about where we would be if it weren’t for COVID is such a strange phenomenon. So, rounding out this interview, I’d love to know – what makes y’all passionate about housing justice? Is there something particular about housing justice in the South that you’ve noticed?

Ashley: For me, what’s important is I look at a lot of legal issues holistically. I’m also a social worker, and I have my MSW. Like, it’s not just housing; housing is tied to where your children go to school, if you experience food scarcity, access to childcare services, etc. People are in a very financially fragile state right now, because once you become unhoused with your children, it’s going to trigger a lot of McKinney-Vento and DSS involvement.

Housing is about community. It’s so much more than just a roof and walls. It’s about people’s whole lives. Maybe their family has lived there for generations, they want to stay in the community, but they’re getting priced out as the neighborhood gets gentrified. To me, housing is one of the core components of people being in community and living happy whole lives.

Glynnis: For me, I’m all about access to educational opportunities. That’s what I went to law school to do, so like Ashley, my focus was on children. When I was younger, I didn’t understand how much housing impacts the rest of our lives and how where we grow up affects our trajectory. Knowing all that, I want people to have housing in safe places, kids to have housing that connects to good school districts, and college/postsecondary opportunities. One thing about the South is this misconception that we are a place of affordability. Nationally, if you look at living in South Carolina versus living in California or New York City, this is an affordable place. But if you zoom in and actually look at South Carolina salaries and like how many jobs are available within the state, it looks less affordable. For the residents who live here, I think that we can do more to dismantle that misconception.

In Code Switch, there’s a phrase that says, “housing segregation affects everything.” Like, segregation still exists, because it was so baked into our system, and especially in the south. We’re hesitant to like, make changes and recognize that the segregation that existed in the 60s continues to live on because we never made policies to remedy the segregation except for the schools.

Ashley: Yeah, think a lot about credit scores. You know, the place you could get with a 600 credit score versus an 800 credit score is wildly different. Even if you could produce the money, but you have a poor credit score, they don’t care. Where you live affects your opportunity in general, which is a huge issue.

A federal law known as the McKinney-Vento Act gives students who don’t have permanent housing help in enrolling, attending, and succeeding in school. The law states that schools must make sure that all students have the same chance to receive a free and appropriate public education, even when difficult times have caused students and families to lose their permanent homes. Students in this situation must be given extra help, and this brochure describes some of their rights provided under the law.

I completely agree, thank you so much for y’alls perspectives on that. To round things out on more of a hopeful note, what makes you both hopeful for the future of housing justice and liberation?

Ashley: I think people see what we’re doing and where we’re going in the vision. I think we’re now having these conversations that used to be siloed. Everyone is competing for the same resources, but now we’re all trying to amplify each other. If we think you could have a legal issue, I’m gonna go refer you to legal services. And let’s talk to the library because they have social workers. I think we’re all getting in community with each other.

I’ve met a lot of great people who are like, “I’m going to use my degree,” “I want to use this experience that I have,” or “I’m going to use my organizing skills to get folks together.” So, I’ve been excited about that.

Glynnis: I echo all this. My big criticism as a teacher was that everybody is working in silos, and it feels like everybody’s doing their own thing. And what we really need to do is bring people together, and then elevate those voices. And somehow, we’ll make a way out of that. So yeah, working and meeting everyone in the space and seeing their passion has really helped me to stay motivated and get this work done. Housing is, in my mind, a fundamental right. In this day and age, you can’t survive without a roof over our head, running water, and access to heat and air conditioning. We need that to survive. You don’t know what everyone’s going through and just being able to like, make some impact – that’s really nice.

Thanks so much to Glynnis and Ashley for discussing their experience as navigators with us. Visit the NAACP Navigator Page to find more information about the program.

To learn more about rental realities and eviction in South Carolina, visit our SC Tenant Voices page for details.